It had been a tumultuous year, but Justin Trudeau’s Liberal Party was still sitting comfortably in the polls, almost ten points clear of the Conservatives, and he could reflect on the fact that all but two first-term majority governments in the entire history of Canada had been re-elected. Christmas vacation 2017–18 for the Trudeau pack — Justin; his wife, Sophie; and their children, Xavier, ten years old, Ella-Grace, eight, and Hadrien, three — was a very different affair than the previous year, when they had accepted an invitation from the Aga Khan to holiday with family and friends on the Ismaili spiritual leader’s private Caribbean island, Bell Island, using his private helicopter to get there. Trudeau was eventually found guilty of contravening the Conflict of Interest Act on four counts for his little family vacation and so decided to play it safe this time around, skiing on the slopes of Lake Louise in the Rockies.

The Liberals have always had a vulnerable heel when it comes to entitlement issues. The NDP leader Jagmeet Singh summed up the public mood: “It just seems there’s these two worlds. There’s the world everyone else lives in, where people are struggling to make ends meet. And then there’s the world where people who are wealthy and well-connected and powerful think the laws don’t apply to them.” But while there was widespread disapproval about the Trudeau family visit with the Aga Khan, the ethics commissioner’s censure did not appear to shift vote intentions — at least not immediately.

The Trudeaus headed to the remote, back-country resort Skoki Lodge, accessible only by ski and sled. In contrast to the luxury of the previous year, conditions at Skoki were spartan, with no Wi-Fi, no power, and no running water. “The outhouse at 25 below was great for the kids,” joked Trudeau. The prime minister is an inveterate user of social media, but in its absence he read vociferously and scribbled away at those soft-cover puzzle magazines you can buy at newsstands. His usual exercise regime of boxing and yoga was replaced by skiing and snowboarding.

He returned to work in a buoyant mood. When asked if he was worried that the government’s credibility was being impacted by a recurring habit of tossing election pledges into a boneyard of broken promises, he was unapologetic. “We put forward an incredibly ambitious agenda for 2015, where we laid out a plan for a government that was going to be active in changing things and making things better for people in a whole bunch of different ways, and we’re delivering on those commitments. We’re halfway through the mandate. We’ve done an awful lot, there’s still more to do but I am confident that we’re going to achieve the things Canadians expected us to do,” he said.

He appeared remarkably unruffled at being one of the most scrutinized people on the planet

Trudeau was elected on the back of the slogan “Hope and Hard Work.” When he stuck to that message track — labouring with diligence and discipline to promote a more compassionate Canada than the one bequeathed by his predecessor, Stephen Harper — he won acclaim at home and abroad. He appeared remarkably unruffled at being one of the most scrutinized people on the planet. “Justin has not changed. Of all the people involved in this process, he’s changed the least,” said Tom Pitfield, a lifelong friend of Trudeau’s who is now part of his political inner circle. “He’s the exact same person who tried to win that boxing tournament — he’s just become more disciplined.”

But political troubles are not like flurries on a river — one moment white, then melted forever. They are more like mounds of thick, wet slush that pile up until they block a government’s progress. The blizzard that blew away any complacency in Liberal ranks, and forced Trudeau and his advisers to recognize that victory at the next election was not preordained, was the prime minister’s ill-fated passage to India in February 2018. What should have been a routine foreign trip, with the prize of securing closer trade ties to one of the world’s fastest-growing economies and endearing the prime minister to Indian Canadians across the country, ended up highlighting the more flaky side of Trudeau’s personality. The colourful spontaneity Canadians had once found refreshing was suddenly ridiculous for many.

If, as Walt Whitman suggested, human beings are prone to contradict themselves because they are large and “contain multitudes,” Trudeau is not that unusual. But if his first fifteen months in office displayed the Jesuit restraint more typical of his father, the visit to India in February, with the whole family in tow, saw his impetuous side come to the fore, with near-disastrous diplomatic consequences. Trudeau said that the impetus behind the visit was his own memories of going on trips with his father. “Going through it now, having my family with me, makes me a better politician and a better dad,” he said by way of explanation.

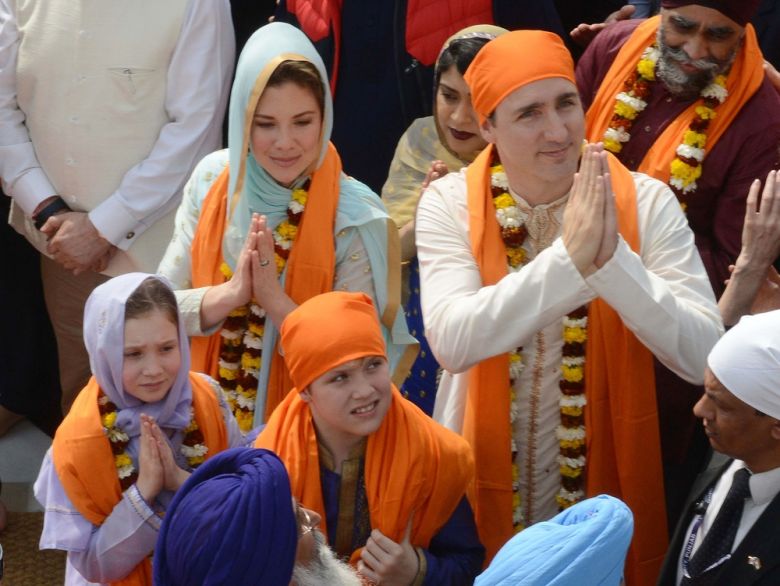

The family was pictured in lavish local costumes in the shadows of the subcontinent’s great sites. The eight-day visit was characterized by a threadbare itinerary that looked increasingly like a taxpayer-funded family vacation. Coming so soon after the Aga Khan scandal, it felt to many Canadians like a thumb in the eye. As the attire grew more exuberant, so did the sniping that the Trudeau tour was “too Indian, even for an Indian.” The extremely light official diary allowed the Trudeaus time to pose with some of India’s top movie stars, like Shah Rukh Khan, who wore a sober Western-style black suit while the Trudeaus wore braided saris and sherwanis. The prime minister capped it off with a performance of bhangra dancing that struck many people as being a Bollywood move too far.

Some senior Liberals back in Ottawa lifted their heads from their hands long enough to point the finger of blame at Sophie for ordering the over-elaborate costumes and persuading the whole family to wear them. “I think there’s no question that was more her than him,” said one Liberal MP. “But, look, he wasn’t forced to wear any of that stuff. There’s a theatrical side to him that likes ingratiating himself with people.” (Sophie Grégoire Trudeau was asked to contribute to this book but declined.)

It all smacked of the kind of cultural imperialistic tourism that Mark Twain lampooned 150 years ago in The Innocents Abroad: “In Paris, they simply opened their eyes and stared at us when we spoke to them in French! We never did succeed in making those idiots understand their own language.”

When it was revealed that an Indian Canadian once convicted of the attempted murder of an Indian politician in British Columbia had been invited to an event at the High Commission in New Delhi, the trip was roundly condemned as a disaster. Jaspal Atwal, a former member of the extremist International Sikh Youth Federation, deemed a terrorist group in Canada and India, attended a reception in Mumbai, where he was photographed with the prime minister’s wife and Indian-born cabinet minister Amarjeet Sohi. He was also invited to the event in New Delhi, but that invitation was quickly rescinded once the pictures from Mumbai were made public in Canadian media and Atwal was identified as having been convicted of the attempted murder of Malkiat Singh Sidhu, a Punjab cabinet minister, during a visit to Vancouver Island in 1986.

There may have been extenuating circumstances. The Prime Minister’s Office encouraged the Canadian national security adviser, Daniel Jean, to talk to reporters — briefings in which Jean suggested that elements within the Indian intelligence service may have been happy to see Atwal embarrass Trudeau for being soft on Sikh separatism. Atwal’s name was removed from a blacklist, thus allowing him into India, and Jean suggested he had been cultivated by diplomats at the Indian consulate in Vancouver.

But as any veteran of political campaigns knows, when you’re explaining, you’re losing. The impression left with many Canadians was that Trudeau had embarrassed himself, which was his prerogative — and the country, which was not. “If they had Googled the name, this guy (Atwal) would have shown up in two seconds,” said Garry Keller, who was a former chief of staff to Conservative foreign affairs minister John Baird. Trudeau’s erstwhile allies at the Toronto Star wrote it off as “the least successful foray into that country since the repelled Mongol invasions.” Similar headlines ran in newspapers around the world. Trudeau said his one regret was he didn’t take more suits to India.

The impression left with many Canadians was that Trudeau had embarrassed himself

When the final bill came in, the trip was revealed to have cost around $1.5 million, including $17,000 to fly Vancouver celebrity chef Vikram Vij to help prepare Indian-inspired meals at the Canadian High Commission. As the opposition pointed out, there were, presumably, plenty of cooks in India who knew the recipe.

“We walked into a buzzsaw — (Narendra) Modi and his government were out to screw us and were throwing tacks under our tires to help Canadian conservatives, who did a good job of embarrassing us,” said Gerald Butts, in his evaluation. “But none of that is the core issue …. Nobody would remember any of that had it not been for the photographs. We should have known this better than anybody — in many ways we’d used this to get elected. The picture will overwhelm words. We did the count — we did forty-eight meetings and he was dressed in a suit for forty-five of them. But give people that picture and it’s the only one they’ll remember.” Prince Harry, so often depicted in a Savile Row suit, probably felt the same way about the pictures of him on the one occasion he dressed as a Nazi.

The impact was immediate in the polls. What had been a comfortable Liberal lead over the Conservatives was whittled away and the parties spent the following months in a statistical tie. New Conservative leader Andrew Scheer had come in on cat’s paws after winning a lengthy leadership race in May 2017 and had spent most of the intervening period consolidating his existing base rather than wooing new voters. Yet suddenly, through no particular enterprise of his own, Scheer was a real contender to be Canada’s next prime minister. It was a classic example of a recurring paradox at the heart of Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government: brave moves — such as his decision to hold a town hall in Nanaimo, B.C., in early February 2018, in front of an audience that was deeply hostile to his government’s decision to back the construction of a crude oil pipeline through the province — that are often undone by silly, unforced errors.

His father, Pierre, had faced an election that was far tighter than it should have been in 1972 — just four years after being elected on a wave of “Trudeaumania.” Visiting British journalist Jerome Caminda discovered an angry country. Trudeau dominated the front pages of Canadian newspapers through his “flair for physical activity” and his unerring sense of drama, Caminda wrote, but he was losing his audience. Still,Trudeau senior was seeking re-election at a time when unemployment remained high, even as inflation was rising. By contrast, his son has presided over a period of relatively strong growth, with inflation at benign levels and unemployment lower than at any time since the mid-1970s. In the absence of strong economic headwinds, the loss of Liberal audience could be blamed squarely on the prime minister.

Trudeau’s handlers continually reminded him that his sense of humour was no laughing matter, advising, “You have many attributes but you’re not funny — stick to the script.” Yet he struggled to comply, as with his weak attempt at humour with the lady in a town hall who talked about “the future of mankind,” only to be corrected by Trudeau, who said he preferred “peoplekind.” The seemingly innocuous comment drew ire around the world before Trudeau even had the chance to explain he was joking. “How dare you kill off mankind, Mr. Trudeau, you spineless virtue-signalling excuse for a feminist,” wrote professional controversialist Piers Morgan on MailOnline, the most visited English-speaking newspaper website in the world.

Veterans inside the Liberal government kept their heads while the less experienced were losing theirs. “The India trip plays into a narrative that Trudeau’s not serious, but voters will not be saying in the polling booth, ‘All things being equal, I’d like to vote for him but those costumes in India were so fucking stupid.’ Those people don’t exist,” said one battle-scarred campaign vet. But the backlash was an indication that a politician who has been a pioneer in the use of political image management on visual-based social media had gone too far.

As traditional media budgets have shrunk, and new outlets for visuals multiplied, politicians have more ability than ever to communicate directly with voters. Trudeau has taken full advantage. An analysis by researchers Mireille Lalancette and Vincent Raynauld of 145 Trudeau Instagram posts in the year after his election revealed a shrewd strategy to build a positive, optimistic view of the new prime minister and Canada. The photos taken by official photographer Adam Scotti were edited strategically to showcase a “dynamic and outgoing” leader, tending to his duties with “seriousness and vigour.” Elements of Trudeau’s personal brand were highlighted — youth, athleticism, open-mindedness, empathy, a sunny disposition, and support for feminist causes permeate the pictures. Trudeau is an ardent runner and jogs wherever he happens to be in the world. By pure coincidence, a photographer seems to be available on every occasion. Close to half the pictures contained patriotic symbols. Nothing is left to chance — a picture of Trudeau jogging with Mexican president Enrique Peña Nieto featured the prime minister in a pair of Rugby Canada shorts and a T-shirt from the Saskatchewan Jazz Festival. The Prime Minister’s Office tweeted directly to both organizations along with the picture.

This was hardly the first time that a Canadian prime minister had tried to manipulate his or her image. William Lyon Mackenzie King set up the Bureau of Public Information in 1939 to monitor public opinion. The Harper Conservatives became experts at precisely micro-targeting the voters they needed — slicing and dicing the electorate because they knew who their supporters were, where they lived, and whether they were likely to vote, thanks to a voter information database that was the envy of their rivals. But Trudeau took political image-making to another level. One stream of posts saw him expressing reaction to national and international events like the Fort McMurray fires or the Bataclan terrorist attack in Paris. “They highlight his compassion, empathy and sensitivity,” said the authors of the Instagram study.

By the end of 2017, one columnist calculated that Trudeau had wept openly, or had his eyes well up, at least seven times on camera. In October, he cried as he spoke about the death of his friend Gord Downie, lead singer of the Tragically Hip; a month later, he was in tears as he apologized to residential school survivors in Newfoundland and Labrador; and a few days later he was dabbing his eyes with Kleenex as he delivered an apology to members of the LGBTQ community for decades of sexual persecution by the Canadian government. These were meaningful interventions for the people whose lives had been impacted — but they were frequent. Trudeau’s demonstrative nature expanded the palette of emotions accessible to Canadian prime ministers — it was hard to imagine his predecessor exhibiting such vulnerability, or even his own father. But the prevalence of occasions where he brought himself to tears in late 2017 led some to question his sincerity.

Another category of pictures featured Trudeau taking part in pre-planned events like the Pride Parade or visiting baby pandas at the Toronto Zoo. They showed him in casual attire, usually in a shirt with the sleeves rolled up and no tie, “at ease interacting with those around him.” Some of the posts offered an insight into his family life — trick-or-treating on Halloween or taking part in Father’s Day celebrations. “These posts give an impression of normal family life that appeals to voters who see their own lives reflected in the Trudeau family,” said the authors of the Instagram study.

With such a carefully calibrated spin machine at his disposal, it remains a matter of debate how Trudeau, with his bulging Tickle Trunk, got it so wrong in India. Perhaps it was as simple as voters not seeing their own lives reflected in the images of the Trudeaus, dressed up like Bollywood extras, in front of the Golden Temple in Amritsar. One Liberal MP said Trudeau has gone to the empathy well once too often. “What I get at the doorsteps is, ‘I don’t want to hear any more apologies. I don’t want to see any more pay-outs. I don’t want any more political correctness. Do them but talk about what you’re doing on the economy. Talk about the things that make a difference in my life.” The MP said he has a large reservoir of respect for Trudeau. “He’s a quick study and he’s got more depth than people give him credit for.” But he said the opposition tag of him as a lightweight is always there. “That ‘lightweight’ business is always at the back of people’s minds and India confirmed the lightweight image.” Whatever the explanation for the trip’s shortcomings, it was more bad news to add to an accumulating pile. The potential for spontaneous combustion is always there for Canada’s twenty-third prime minister.