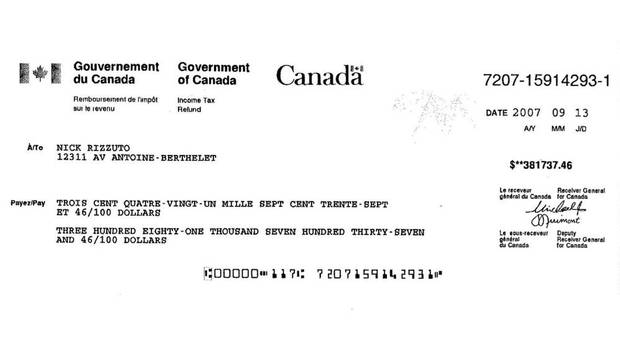

The Canada Revenue Agency issued a $381,737 cheque to mob boss Nicolo Rizzuto, sparking fears that the tax-collection organization had been infiltrated by organized crime, retired tax auditors said.

At the time of the payment in 2007, the agency had a $1.5-million lien on Mr. Rizzuto’s home, which meant he was not eligible for a reimbursement, according to court records and retired officials.

A CRA auditor who specialized in tracking criminal figures, Jean-Pierre Paquette, first spotted the payment as he was going through Mr. Rizzuto’s file. Given the patriarch of the Mafia family was in jail, Mr. Paquette spoke to Mr. Rizzuto’s lawyer before going to his house to recover the cheque from his wife and daughter, who complied.

“I can guarantee you that in order to issue a cheque for $382,000, you need approvals; no one can wake up one day and do that,” Mr. Paquette, who retired from the CRA in 2009, said in an interview. “How did that one manage to go through the safeguards? It remains a mystery.”

The CRA has been shaken by allegations that its Montreal offices were infiltrated by a group of corrupt employees who offered favours and special deals to taxpayers in exchange for kickbacks. An investigation launched in 2008 resulted in fraud and corruption charges against six former officials. The cases are all still before the courts.

Another former member of a CRA unit that focused on criminal figures, Robert Martin, said the cheque to Mr. Rizzuto raised questions inside the agency.

“Normally, when there is a debt, we don’t send a cheque,” he said in an interview.

A copy of the CRA cheque to Mr. Rizzuto was obtained by Radio-Canada and shared with The Globe and Mail. The CRA refused to provide more details on the cheque or state whether it launched an internal investigation to find out who had approved the payment, citing confidentiality laws.

Mr. Rizzuto pleaded guilty to tax evasion three years later, paying a fine of $209,200 after failing to declare $728,000 in interest revenues on $5-million in Swiss bank accounts. He was assassinated in late 2010, at the age of 86, by a gunman who shot him through a window in his house.

The CRA’s Montreal offices were allegedly infiltrated by employees who offered favours and special deals to taxpayers in exchange for kickbacks.

Mr. Paquette and Mr. Martin are concerned about the CRA’s dedication to fighting organized crime. Until their respective retirements in 2009 and 2013, the pair spent much of their careers in a unit called the Special Enforcement Program (SEP). Created in the 1970s, the SEP focused on “taxpayers suspected of, or known to be, deriving income from illegal activities.”

However, the CRA has dismantled the SEP as part of a reorganization of its activities, brought about by a recent wave of administrative changes and cutbacks. According to CRA documents, the agency transferred the “audit work that was previously carried out by criminal investigators into the regular audit stream.”

Mr. Paquette expressed doubts that regular CRA auditors can replace the work of the specialized unit. He said the only perk that comes with auditing criminal figures is a regular dose of adrenalin, something that does not interest most CRA officials. Over the years, SEP auditors have gotten into heated situations, including receiving death threats and having guns drawn on them.

The SEP had a special status inside the CRA. During his career, Mr. Paquette went after mobsters, fraudsters, pimps and other criminals to recoup unpaid taxes.

Mr. Paquette said going after the proceeds of crime is a key part of law enforcement and sends a clear message of deterrence to criminals. He added that he was “totally bewildered” when he learned of the SEP’s demise.

“I still can’t understand why this is happening,” he said. “They are using the budget cuts to state that the unit is no longer needed.”

Mr. Martin, who retired from the CRA last month after a 35-year career, said the reorganization hindered his work on a major file. He said members of the SEP “were not welcomed” in the regular audit stream, given they used different, more aggressive auditing techniques when they delved into the books of known criminals and their associates.

He said that when members of the criminal underworld found out about the SEP’s shutdown, they likely “popped champagne.”

“When Ottawa made this decision, they didn’t think it through. They didn’t have a Plan B to determine who would now be in charge of these types of files,” Mr. Martin said.

Over the years, SEP officials built relations of trust with police investigators. Without the SEP in place, Mr. Martin said, police bodies “aren’t interested in passing along their files to auditors.”

Toward the end of his career, in the mid-2000s, Mr. Paquette was seconded to the massive police-led anti-Mafia operation called Colisée. It was during that period that he discovered that an anonymous informant had warned

Mr. Paquette said he relayed the information to his superiors at the CRA, but that nothing of consequence happened for months. He informed another superior in 2007, which finally got the ball rolling.

“I had been told at first to forget about it,” Mr. Paquette said. “I was afraid that this was going to end up in the bottom of a drawer somewhere.”

The RCMP launched its investigation in 2008, and charged six former officials from the agency’s Montreal offices on fraud and corruption charges in 2012 and 2013.

In a 2010 internal audit of the SEP, the Canada Revenue Agency found that the unit conducted 5,000 tax audits between 2004 and 2008 “that resulted in the identification of over $428-million in federal tax revenues owing.” However, the audit found criminals frequently failed to pay back the full amounts to the CRA, and that the agency did not adequately publicize its work.

“With respect to deterrence, there appears to be little awareness on the part of the public about the Agency’s enforcement capacity. Efforts to publicize convictions of prosecuted cases lack a proactive engagement of the media,” the audit said.

CRA’s $381,737 cheque to Mafia boss raised red flags, ex-auditors say

Laissez un commentaire Votre adresse courriel ne sera pas publiée.

Veuillez vous connecter afin de laisser un commentaire.

Aucun commentaire trouvé