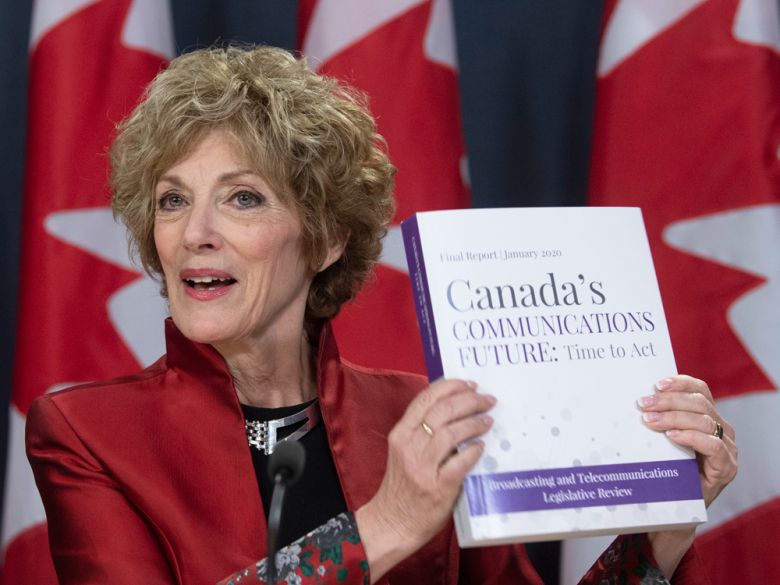

Putting aside the 97 recommendations contained in Wednesday’s final report from the Broadcast and Telecommunications Legislative Review Panel, Communications Future: Time to Act, the document reflects three important long-term shifts in the communications landscape.

The first relates to the sheer scope of media communication in our lives. This kind of report was a dime a dozen during the Cold War. But in those days, this was a lower-stakes game, as the calls for reform mostly were about tinkering with the formula governing how many times TV networks were required to air The Beachcombers and Check It Out!. Entertainment media was a one-way information flow. And consuming it represented a discreet and limited form of regulated activity, like driving on public highways or visiting a national park.

That has completely changed. Many of us spend our entire professional workday surrounded by digital media that blend entertainment, news and interpersonal communication in complicated ways. In 2020, “the communications sector” is inextricably tied with every aspect of our daily existence.

From the moment the world wide web was born in the 1990s, the CRTC, like its counterpart national regulators, had no idea what to do with it. The old regulatory model, which was based on controlling the content served up by a relatively small number of media spigots (radio and TV stations), didn’t scale well to a medium with millions of channels, the vast majority of them based outside Canada’s borders.

But that, too, has changed. And here we get to the second massive shift in the communications landscape signalled by this week’s report.

In recent years, the million-channel universe has shifted into an oligopoly dominated by the likes of Netflix, Apple, YouTube, Spotify, Facebook, Crave, Disney and Amazon Prime. From a regulator’s point of view, it now somewhat resembles the limited set of legacy spigots that dominated the media landscape in the pre-web era. It doesn’t hurt that all of these companies distribute their content over cable and cellular networks that are themselves creatures of highly regulated oligopolies.

The central thrust of the report, which is hard to dispute, is that it’s time to end the piecemeal approach to media regulation represented by the Broadcasting Act, the Telecommunications Act, and the Radiocommunication Act, as well as the alphabet soup of associated agencies and funding programs. Unfortunately, the recommendations are so broad that they invite suspicion about whether the real goal is social engineering. Much of the report seems to consist of pointless virtue signaling. The word “Indigenous” appears more than 90 times, for instance — almost invariably as a complete non sequitur. The word “reconciliation” gets 12 mentions.

The recommendations invite suspicion about whether the real goal is social engineering

It’s unsettling to observe how much power the panelists are seeking for the new “Canadian Communications Commission,” as the CRTC is proposed to be renamed. Its remit would extend to “audio, audiovisual as well as news content,” including pure text. “Media content undertakings” generating significant Canadian revenue would be required to register with the agency, and subject themselves to Canadian content requirements and a vaguely defined regime of content control described under the Orwellian heading of “social harms.” In theory, that might even extend to my own website, Quillette, which is based in Australia. Thanks, but that’s a hard pass.

The panelists also propose the creation of something called a Public Interest Committee, which sounds like a national version of the diversity star chambers that have metastasized into a much-loathed form of parallel governance at the CBC. Recommendation 94 contains a cryptic reference to “international cooperative regulatory practices on harmful content,” which seems like a coded reference to the various UN instruments demanding censorship of one kind or another. Again: hard pass.

In another age, this is where the analysis would end: Once again, public officials are trying to block speech and control private media, and so we all need to rally for free speech and commerce. Yet part of me is sympathetic to the panelists’ case. And here we get to a third massive shift in the media landscape.

Until fairly recently, the business of censorship was purely a government operation. But when people under 30 now talk about “free speech,” they’re just as often talking about what’s allowed on social media. One of the biggest recent free-speech cases in Canada, for instance, had to do with Twitter’s decision to ban Vancouver-based feminist Meghan Murphy, not with any government law or court ruling.

Once again, public officials are trying to block speech and control private media

In this vein, this week’s report recommends that the Canadian Communications Commission regulate the “terms of trade” and power “imbalances” so often exploited by social-media platforms. In some cases, that might not be a bad idea. Many Canadian citizens and businesses now rely on social media as a necessary communications and commercial service, like the phone network. It’s not always clear why it shouldn’t be regulated as such, especially when Twitter arbitrarily shuts people down for ideological reasons.

No one should trust any agency of government to regulate speech. Just this week, we learned of a bizarre investigation into Ezra Levant’s alleged violation of election laws … for selling a book. I’m no fan of Ezra’s Rebel site. But free countries don’t ban book sales. Ever.

Yet even as we remain vigilant regarding government censors, we should also keep one eye out for the digital oligopolists who seem equally eager to stifle speech for their own purposes. In a perfect world, the proposed new Canadian Communications Commission might bring corporate censors to heel. Too bad that’s probably not the world we inhabit.

• Email: jonkay@gmail.com | Twitter: JonKay