Our first prime minster, Sir John A. Macdonald, said “A public man should have no resentments.” His seething successors demonstrate that this adage is in desperate short supply in Canadian politics today.

Faithful to the partisan glue binding them to their parties, our political class is doing everything possible to diminish, demean, and destroy the precious commodity they actually hold in common: their own political integrity. In their relentless attacks on everything and everyone on the opposite political divide, they continue to devalue the basic political currency – trust – essential between electors and elected in a democracy. We, the voters, are the losers.

Think of it in marketing terms. If one fast-food chain levelled charges of systemic food poisoning at a competitor, how long would it take before a counter-charge flew back and customers started cooking at home?

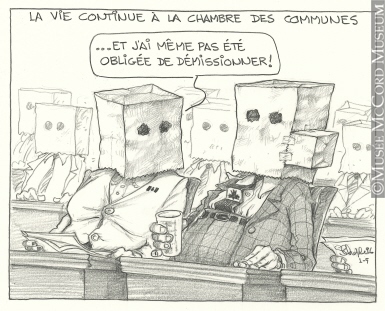

Our MPs and parties are undermining the long-term brand of political and public service in the search for short-term political advantage. The result is more citizen cynicism, voter apathy, and polarization.

Trust in Canada’s Parliament and MPs was among the lowest of some 26 countries in a polling survey conducted late last year. Another survey last spring found a twenty-point drop in democratic satisfaction in Canada in eight years to just over half of Canadians.

The reasons for this are both systemic and cultural. A winner-take-all political system requires disciplined parties cadging for every vote they can get. Minority parliaments accentuate the rancour while majority parliaments cement the arrogance and we’ve had both in the past seven years. Advancement in the House of Commons – on both sides – is never hurt and generally helped by excessive partisanship. Media outlets put a premium on conflict and division to attract viewers and readers (it’s a business after all), and simplify issues for easier comprehension and communication.

Yet, for all its faults, partisan politics has its place. Promoting your ideas while challenging a political opponent’s own can clarify choices and send important cues to voters in a democracy. Principles, if not always ideology, are a valuable basis upon which to make policy choices.

But partisanship today revels in personal defamation and worse, voter misrepresentation. Transparency is the new ‘gotcha’ game in the nation’s capital.

For several months now, the heat of inflated expense claims in the Senate and a criminal investigation of the Prime Minister’s former chief of staff have dominated headlines. New rules will now be put in place, more reports will be filed, and angry citizens will hopefully be placated – until the next time. Meanwhile, the hunt for a new victim, real or imagined, goes on and political trust is collateral damage.

As for voter misrepresentation, the robocalls episode exposed a seamy underside to the organizational quest for votes all parties undertake. Once parties sought to identify supporters and induce them to vote; now they identify non-supporters and suppress their vote.

What’s to be done? A decade ago, democratic reform studies and initiatives were underway in many provinces and in Ottawa. While most focused on changing the electoral system to a form of proportional representation, one went further in examining the core institutions and processes underpinning democracy. That was New Brunswick and its Commission on Legislative Democracy. It recommended not just a new voting system but a new electoral boundaries act, an election commission, enhanced roles for MLAs and the legislature, a referendum law, and even putting civics classes back into the classroom. Three governments, one Liberal and two Conservative, have successively enacted aspects of that report.

A thorough airing and critical analysis by a group of respected and engaged Canadians – young and old – would serve us all. It would focus not on what was wrong, but what could be made better.

It is not too much to ask, in a democracy, that our elected representatives leave it a bit better when they are done with it?

After all, transparency really means being able to see through someone or something. Canadians can and they don’t like what they see.

David McLaughlin was deputy minister to the New Brunswick Commission on Legislative Democracy.

In Canada’s damaged democracy, partisanship has taken the place of trust

David McLaughlin

Laissez un commentaire Votre adresse courriel ne sera pas publiée.

Veuillez vous connecter afin de laisser un commentaire.

Aucun commentaire trouvé