As a personal story, it's not a bad movie, but one needs knowledge of history not to fall prey to Félix Rose’s romanticized point of view.

I would not have gone to see Les Rose, Félix Rose’s documentary about his father Paul and the Rose family, if it weren’t for my job. This is not to say that such a movie should be banned or even that it should not have been produced by the National Film Board of Canada. It’s just that I don’t want to be part of any whitewashing of the Front de libération du Québec.

My cousin was married to one of the founders of the FLQ, Georges Schoeters, and I know the pain terrorists inflict even on their own families.

Despite the claim, on screen, by Paul Rose’s brother Jacques, that FLQ bombs never killed anyone, in fact, the FLQ killed at least eight people, albeit not all in bombings, and injured many more.

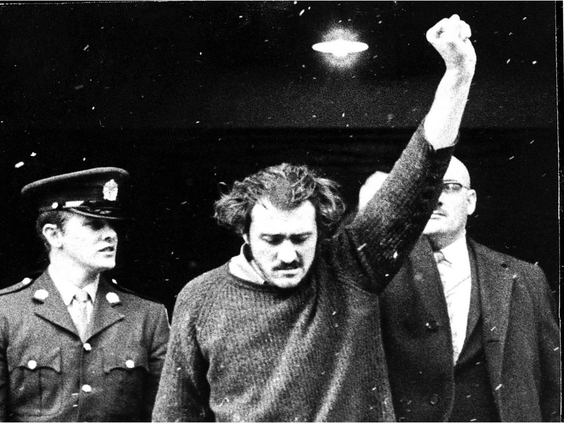

Les Rose avoids describing the FLQ as a terrorist organization. Violence is “direct action.” Revisiting history through the lens of a son’s quest for his father gives the kidnapping and murder of Pierre Laporte a veneer of acceptability by humanizing armed rebellion and presenting it as a legitimate quest for social justice.

The Rose family was a typical working-class French-Canadian family from St-Henri. The men worked like dogs for a pittance under anglo bosses who ran imperialistic companies with an iron fist. But the film shows urban working-class Quebec as it was before 1960 and the Quiet Revolution, before the nationalization of Hydro-Québec, the creation of the ministry of education, the establishment of universal health insurance, all of which had already happened by October 1970.

The Quebec of Les Rose no longer existed when I was growing up in Hochelaga-Maisonneuve in the 1960s and ’70s. Some people were very poor, but there was also hope that Jean Lesage’s Maîtres chez nous would come to fruition. The cause of Quebec independence had its mainstream political organizations — the Parti Québécois was created in 1968 — and no one got arrested for promoting “le Québec libre.”

At least until the FLQ and the October Crisis gave Pierre Elliott Trudeau Grade A-fuel to destroy Quebec nationalism, the effects of which are still felt today with the enshrinement of multiculturalism in the Canadian Constitution, a move I and many Quebecers believe was aimed at drowning once and for all Quebec’s aspirations to succeed as a distinct, social democratic French-speaking society in North America.

As a documentary about a tightly knit family, the film is at times moving. Rose Rose, the matriarch, is portrayed as a formidable force of nature who never turned her back on her sons, never condemned their actions, always fought for their release. Regardless of what one may think about Paul Rose’s crimes, it was cruel not to let him see her on her deathbed, and only to allow him to attend her funeral days later.

Like all movies made about the October Crisis, this one sheds no tears about the main character in the story, Quebec Liberal cabinet minister Pierre Laporte, who died while held by the FLQ’s Chénier cell led by Paul Rose.

His death is glossed over.

To this day, no one knows for sure whether he was murdered — or “executed,” as the FLQ had threatened along with their list of demands — or died trying to escape. This most intimate of documentaries does not lift the veil on this mystery. The kidnappers declared themselves jointly responsible for his death, end of story.

As a personal testimony, it is not a bad movie, but one needs knowledge of recent Quebec history not to fall prey to Félix Rose’s romanticized point of view. It is also important to remember that René Lévesque was a harsh critic of the FLQ. He knew their actions would stand in the way of independence. And they did: The October Crisis helped seal the fate of the 1980 referendum.

But this, Les Rose won’t tell you.