It is painful to be so out of step with many politicians and commentators with whom I normally agree, but I don’t think the unfolding Jody Wilson-Raybould controversy is being evaluated correctly. As I have written here before, Wilson-Raybould committed a number of acts and adopted a number of policies as minister of justice that advanced the interests of the native people, or at least some of the leaders among the native people, at the expense of the Canadian national interest. She incited suspicion about whether she was exercising her powers even-handedly. She had a duty to ensure that the decisions she took were objectively just and fair. I don’t believe she was blameless in these matters, and it would be surprising if that were not part of the motivation in shuffling her to another ministerial portfolio. I appear to be among the very few people in this country who has mentioned this aspect of the controversy, which indicates the extreme reluctance of anyone to touch native affairs policy. That is an aversion the political class and the media will have to overcome, as it is a vital and delicate field in desperate need of reform.

On the ostensible principal cause of the Wilson-Raybould controversy, the treatment of SNC-Lavalin, the government has badly mishandled the case tactically, but has a stronger moral and practical position than it generally gets credit for on three important aspects of it. First, the law forbidding Canadians, and especially Canadian business people, from doing such things as bribery in foreign countries where such unsavoury practices are a condition precedent to doing business at all, when the individuals are only doing so in the legitimate interest of the businesses involved and at no direct profit to themselves, is nonsense. Canada is a G7 country with a number of distinguished international companies and we cannot expect these corporations to compete with one hand tied behind their backs in much of the world. The determination of what constitutes an acceptable ethical climate for the conduct of business resides with the jurisdiction where the transactions take place. It is preposterous for, in this case, a Canadian company to be penalized for conduct in Libya that reflects the commercial customs of that country, even if the same actions in Canada would be illegal. Canada must stop masquerading as the self-elevated eagle scout of world commerce.

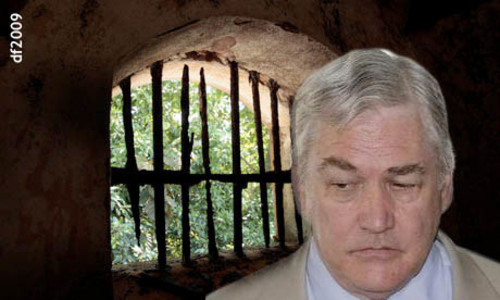

- Conrad Black: SNC-Lavalin is a sideshow to the real Wilson-Raybould issue

- Conrad Black: The Liberals have stumbled their way into a disaster

Second, the option to Canadian prosecutors to impose a fine rather than lay a criminal charge is legitimate and sensible and the media and opposition should stop referring to it as a sleazy, partisan escape hatch for the naughty corporate friends of the Liberal party. Prosecutions are destructive, costly and not infrequently unjust. If the senior officials of our Justice ministry felt they had a legitimate legal grievance against SNC-Lavalin and some of its executives, it is more likely that a fine would be a better response than inflicting serious damage on a corporation with 10,000 Canadian employees and many thousands of shareholders, suppliers and other stakeholders.

No one should imagine that there is any great morally cleansing aspect to a criminal prosecution in a case like this. Where a crime occurs in Canada and there are victims and a requirement for punishment and retribution for justice to be served, especially if any violence occurred, prosecutions must be pursued. But where the interests of a large number of innocent people are involved, as at SNC-Lavalin, and it is essentially an attempt to apply Canadian law to a foreign jurisdiction, a fine is much preferable to a prosecution, and even then can only be justified if there was an unnecessary recourse to distasteful business methods. This practice of the entire political opposition and media of leaping on their soapboxes and screaming for a criminal prosecution is barbaric.

Third, where the national interest or a fundamental point of justice is involved which individual prosecutors or the director of prosecutions could not reasonably be expected to grasp or weigh, it is perfectly in order for the prime minister or a senior person acting for him, such as the principal secretary (Gerald Butts), or clerk of the privy council (Michael Wernick), to review the file. In the SNC-Lavalin case, the question of whether the company would depart Canada, disemploying thousands of people, or would be declared ineligible to bid for engineering business in this country for a prolonged period, definitely engages the national interest. The prime minister, any prime minister, is responsible, above all else, for maintaining and advancing the national interest, which includes any enhancement of the collective welfare and security of the country within accepted legal and moral parameters. This sadistically obtuse, antediluvian claptrap that no one outside the Justice ministry can speak to a prosecutor is bunk, as was the prim righteousness affected by Wilson-Raybould in her recorded telephone-ambush of the clerk of the Privy Council, that she was uneasy about talking with him about the Lavalin case.

Given the importance of the subject, the prime minister should have summoned the minister and the director of prosecutions and whatever independent counsel he thought appropriate. (Wernick suggested “Bev McLachlin,” the former chief justice. I would be astounded if she would have much useful to bring to that subject, but the proposal indicated that Wernick, acting for the prime minister, wanted a balanced legal position, not an improper derailment of a just proceeding, as opponents suggested.) The prime minister should have gone carefully over the case with the minister and the director of prosecutions and specialist advisers and determined if the damage implicit in prosecuting criminally as opposed to a fine was justified, and instructed that the course he thought to be the best reconciliation of the requirements of justice with the overall national interest be followed. He should have been clear about it, kept all the backup material, and been ready to defend his decision in the same terms to the cabinet, the Liberal caucus, Parliament and the country.

There would have been no need for Butts or Wernick to resign. The argument that Trudeau had no right to review the case is spurious: he has an absolute obligation to discharge the duties of his office. (Leaving prosecutors completely free of discreet and principled review leads to the sort of terrorizing prosecutocracy that exists in the United States, where the perversion of the plea-bargain system encourages the extortion of false inculpatory testimony, and prosecutors win 99 per cent of their cases, 97 per cent without a trial because the position of an accused is so hopeless, compared to about a 65 per cent conviction rate in this country.)

In all of the circumstances, the prime minister and his colleagues were justified in throwing Wilson-Raybould out of the Liberal caucus, bag and baggage. Macdonald, Laurier, King, Pierre Trudeau and Brian Mulroney dispatched more talented members of their cabinets justifiably, and for lesser provocations (though not always from the caucus as well). If Jane Philpott resigned as a minister out of solidarity, and her conduct was otherwise unexceptionable, it seems to me that giving her the high-jump from the caucus too was excessive, but there are likely material aspects in her conduct unknown to me.

> La suite sur le National Post.