If Quebec's move really has no impact, why not put it before Parliament for its consent, as Dion did with a similar issue 24 years ago?

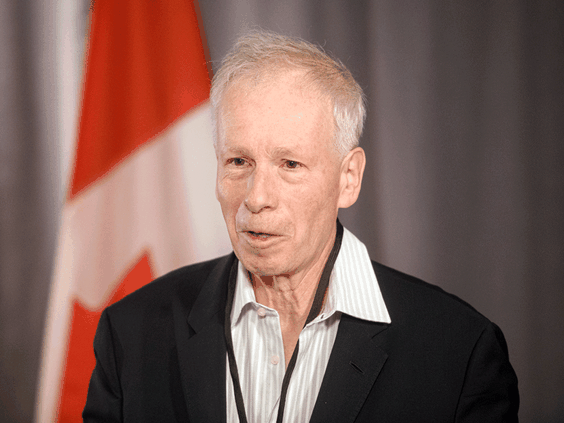

Few people have been as antagonistic to the Quebec sovereignty movement as Stéphane Dion.

Yet, the former Liberal Party leader backs Justin Trudeau’s position on Quebec’s attempt to unilaterally amend the Canadian Constitution to declare the province a nation whose only official language is French.

Blanchet to gauge Parliaments support for Quebec language law reform...

“As long as it is clear that the constitutional rights of Anglophones are not affected, nor any other provision of the Constitution, the prime minister has no reason to oppose it,” he said.

Dion left Trudeau’s government in 2017, much against his better judgment, to become Canadian ambassador to Germany and special envoy to the European Union. (Trudeau’s concern was that Dion’s bluntness would not resonate with the incoming Trump Administration.)

He made his name as father of the Clarity Act, when he was intergovernmental affairs minister under Jean Chrétien – legislation which ensured any future sovereignty referendum will require a clear majority in favour of independence, on a clear question.

The former political science professor earned a reputation as a sophisticated critic of Quebec nationalism, pointing out the inconsistency of the idea that Canada is divisible but Quebec is not.

But his opposition to Quebec’s demands for more autonomy has always been nuanced. He has consistently supported flexibility, particularly on language matters. He once called Quebec’s infamous Bill 101 “a great Canadian law.”

“Identity rather than the division of powers is the source of our unity problem,” he said. “Francophone Quebecers want the assurance that their language and culture can flourish with the support of other Canadians.”

Most people can agree with that point – and on Quebec’s right to declare itself a nation where the official language is French. It is enshrining that concept in the Canadian Constitution unilaterally that has people up in arms.

The federal government’s proposed method of amendment is very different from the one Dion used to handle a similar issue in 1997.

At the time, Quebec announced it would seek a change to the Canadian Constitution to re-organized school boards along linguistic, rather than religious, lines.

Dion’s approach was consistent with his approach to Quebec’s new bill 96 – that the legislation had to guarantee the rights of Anglophones to have English-speaking school boards.

With that proviso, Dion sponsored the legislation in the House of Commons that resulted in a bilateral amendment to section 93 of the Constitution Act of 1867 that deals with education. He used section 43 of the Constitution Act of 1982, since it was a question of abolishing an institution where the government of Canada was the guarantor.

Such a bilateral amendment was possible with the support of the Senate and the House of Commons, and this approach was later used by Newfoundland and Labrador on the same denominational schools issue.

But the Trudeau government is not proposing to strike a bilateral deal that would need Parliament’s consent.

Trudeau intends to use section 45 that allows provincial legislatures to make laws that amend the constitution of that province.

Ottawa’s interpretation suggests that the amendment would not affect the Charter or the division of powers.

But constitutional lawyers like Sujit Choudhry say that declaring Quebec as a nation may not prove to be merely symbolic – and that, if it has substance, it would require support from two-thirds of the provinces, accounting for 50 per cent of the population.

At the very least, he thinks that the justice minister, David Lametti, should seek a reference to the Supreme Court of Canada to get its interpretation. “I don’t think you can be so confident that this is strictly symbolic,” he said.

Dion said that the issue in 1997 was very different.

“We were interrupting the very existence of institutions that were protected in the Constitution at the time,” he said. “This time, why should the prime minister object, as long as the legal opinion he receives is to the effect that the rest of the Constitution is not impacted.”

He pointed out that the courts have already made clear they take into account the specificities of Quebec and the fragility of the French language in North America. “The Supreme Court has said that even if the population of Quebec may be considered a nation, that does not change the fact that there is no right to unilateral secession and that modification of the Constitution would be necessary for secession to be legal,” he said.

But if this move really has no impact, why not put it before Parliament for its consent, as Dion did 24 years ago?

The reason Trudeau has not followed his former minister’s precedent may well be because he does not think he has the support in either the upper or lower house – and he does not want to upset Quebec voters ahead of a general election.

• Email: jivison@postmedia.com | Twitter: IvisonJ