In the 1995 Quebec referendum, Stephen Harper’s Reform party pushed the Chretien government to recognize 50% plus one as the margin of victory for separatists, parliamentary records show.

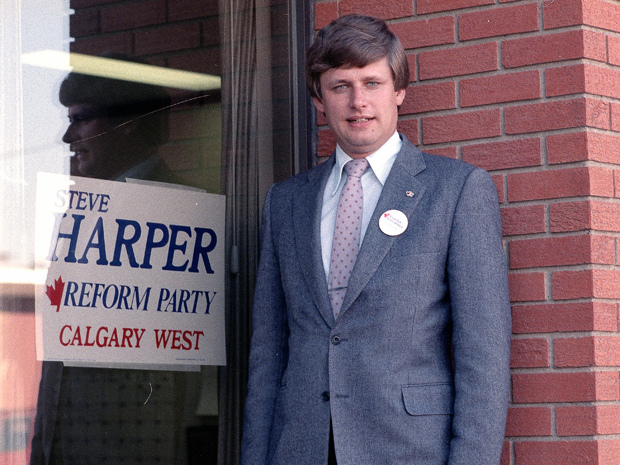

Harper was national unity critic for Reform during that tumultuous period and often spoke for the party during the referendum that nearly led to the breakup of Canada.

Reformers advanced a two-pronged strategy: They warned of how negotiations following a breakup would not necessarily be easy for Quebec, and they promised that, if Quebecers chose to stay in Canada, a Reform government would give more powers to all provinces.

Nearly 20 years later, Harper’s positions from that period are in the spotlight as he faces the possibility of another Quebec referendum — this time, as prime minister.

Quebecers will go to the polls April 7 and if Premier Pauline Marois wins a majority, it’s possible she’ll eventually stage another referendum.

On Friday, The Ottawa Citizen asked the prime minister’s director of communications, Jason MacDonald, to explain Harper’s 1995 position and also whether he currently supports the federal Clarity Act. That statute, passed by Parliament in 2000, stipulates that the federal government will only negotiate Quebec sovereignty if separatists win a “clear majority” in a referendum with a clear question. However, the law does not specify what percentage of the vote would constitute a clear majority.

MacDonald declined comment. “Your question is clearly intended to draw us into the election in Quebec and we have no intention of doing so as we’ve said a few times now,” he said in an email.

In addition to Harper’s stance during the 1995 referendum, he also introduced a private member’s bill in Parliament in 1996, shortly before he temporarily quit politics to join the National Citizens Coalition.

Under his bill, the Quebec Contingency Act, future federal governments would not recognize a Quebec referendum with an “ambiguous or unclear question.” As well, the bill said that if the federal government wasn’t happy with Quebec’s referendum question, it would hold a “parallel referendum” in Quebec on the same day as the provincial referendum.

That federal referendum would have a simple question: “Should Quebec separate from Canada and become an independent country with no special legal ties to Canada?”

It would also include a second question: “If Quebec separates from Canada, should my community separate from Quebec and remain a part of Canada?”

Harper’s bill specified that if there were no concerns about the ambiguity of either the Quebec or federal referendum questions, a “majority of the ballots cast” would be the benchmark for a successful Yes vote.

Harper’s bill, like most private members’ bills, went nowhere. But it provides a glimpse of his thinking at that time.

Reform leader Preston Manning made it clear in his own memoirs where he stood on the question of what would constitute a margin of victory in a Quebec referendum.

“I felt strongly that the growing ambiguity concerning the meaning of ‘Yes’ and the meaning of ‘No,’ and the dividing line between them, was dangerous, especially to the federalist side,” he wrote in Think Big.

“As a democrat, I believed that issues should be decided, if at all possible, by a simple majority vote — 50% plus one” vote.

If Quebec separates from Canada, should my community separate from Quebec and remain a part of Canada?

“Since the federal Liberals, including Trudeau and Chretien himself, had accepted 50% plus one as the dividing line in the first Quebec referendum on sovereignty in 1980, I felt it was dangerous for the federal government to argue now for some higher majority.”

Harper, Manning’s national unity critic, also believed Prime Minister Jean Chretien’s government should acknowledge that separatists had to attain a victory of 50% plus one for break-up negotiations to start, a former Reform adviser said Friday.

“I asked him about it at some point,” said Tom Flanagan, who worked with Harper in Reform and later managed his leadership races and an election campaign. He is no longer part of Harper’s circle.

“He said you had to do that to discourage strategic voting on the part of voters in Quebec who didn’t seriously want separation but thought that voting yes would give the province a stronger hand to negotiate concessions from Ottawa,” Flanagan said.

The issue came to a head in the House of Commons on Sept. 18, 1995 — several weeks before the referendum — when Chretien indicated he might not accept the results of the referendum because it had a “trick” question that implied Quebecers could separate but still enjoy an economic and political relationship with Canada.

Manning told the Commons that Canadians wanted the referendum to be “decisive and conclusive” and urged Chretien to declare that 50-per-cent-plus-one was “the dividing line” for the vote.

Chretien responded by saying he’d only do that if there was a clear question, but that the one being posed to Quebecers was “clouded.”

Minutes later in the Commons, Harper questioned Chretien and said he was “extremely disturbed” by his answer to Manning.

“We have the prime minister saying that a no vote counts and a yes vote may not count. I ask the prime minister to reconsider that position carefully. Is he not really telling Quebecers that it is easy and without risk to vote yes when that is not the case?”

After nearly losing the 1995 vote, Chretien introduced the Clarity Act to guide federal action in future referendums.

Justin Trudeau’s Liberals support the act but Tom Mulcair’s New Democrats say it should be replaced by a bill that would allow secession negotiations to start if separatists win a bare majority — 50-per-cent-plus-one — in a fairly fought referendum based on a clear question.

Mulcair’s party came under fire from the Liberals in early 2013 when New Democrat MP Craig Scott tabled a private member’s bill, the Unity Act, that would make those changes. The Liberals were particularly vocal in criticism and while the governing Tories appeared to try to stay out of the fracas, cabinet minister Jason Kenney tweeted that Scott’s bill would be “making it easier for provinces to secede from Canada.”

The Tories have tended to shy away from discussing the issue, although in October of 2013 the Harper government intervened in a case in Quebec Superior Court over whether to invalidate Bill 99, the provincial law passed in 2000 as a reaction to the Clarity Act. The provincial law says 50-per-cent-plus-one in a referendum is sufficient to trigger negotiations.

Bill 99 was challenged by Keith Henderson of the now-defunct Equality Party, an anglophone rights party. The federal Attorney General intervened in Henderson’s favor. The federal government’s intervention argues that Law 99 “does not and can never provide the legal basis for a unilateral declaration of independence by the government.”

How Harper’s Reform party pushed Chretien government to recognize 50% plus one in 1995 Quebec referendum

Laissez un commentaire Votre adresse courriel ne sera pas publiée.

Veuillez vous connecter afin de laisser un commentaire.

Aucun commentaire trouvé