Canada has so far managed to avoid the populist disruptions seen in other Western democracies, but the social fabric tying the country together may be starting to fray, a leading expert on the issue said.

In his book Whiteshift, political scientist Eric Kaufmann described Canada as a possible exception to the populist wave in the West, but in a recent interviewwith economist Tyler Cowen, Kaufmann said the precarious status quo is now under threat.

“The idea that English Canada is immune to this is actually wrong and I do think we’re going to see more of it going forward,” Kaufmann said. “The electorate is now more polarized on cultural issues than it’s ever been in Canada. We’ll have to see where that goes, but I don’t think Canada will be the great exception that it has been for much longer.”

As evidence of this, Kaufmann pointed to the newly founded People’s Party of Canada, which advocates for reduced immigration levels; and Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservative government in Ontario, which he said “has elements of this populism.” Ford’s government, though, has mainly steered clear of the immigration issue, except for a brief spat with the federal government over funding for resettling asylum seekers who had crossed the border illegally.

- John Ivison: Think populism’s on the way out in Canada? Its foremost exponent is just warming up

- Appetite for populism on the decline in Canada — except among politicians: report

- Exclusive: The future is populist in this age of disruption, Stephen Harper says in new book

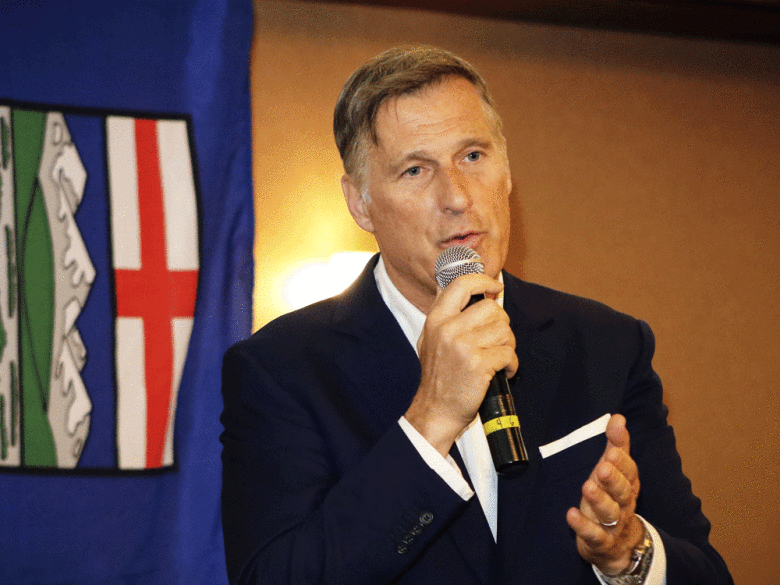

Neither the federal Conservatives or Ford’s PC government have called for a reduction in the amount of legal immigrants that Canada accepts each year. Maxime Bernier, the leader of the People’s Party of Canada, has called for a reduction in the number of immigrants allowed into Canada from 310,000 to 250,000. The current Liberal government hopes to boost the number to 350,000 by 2021.

On Cowen’s podcast, Kaufmann said he’d also noticed recent polling that shows support for immigration isn’t changing much in Canada, but that it is hardening along partisan lines.

“Immigration attitudes are now very different depending if you’re a Conservative or Liberal voter. That didn’t used to be the case even five years ago, so there’s more of a politicization of that issue now,” he said.

A recent poll by EKOS found that nearly 70 per cent of Conservatives surveyed believed that there are too many visible minorities among immigrants, while only 15 per cent of Liberals agreed with that sentiment. Just five years ago, the same poll showed 47 per cent of Conservatives in agreement, alongside 34 per cent of Liberals.

Immigration attitudes are now very different depending if you’re a Conservative or Liberal voter

In his book, which grapples with the end of white majorities in Western societies, Kaufmann devotes a chapter to “Canadian exceptionalism,” trying to explain why the country has managed to avoid a populist backlash despite high levels of immigration.

Kaufmann argues that there is an elite consensus in Canada about multiculturalism and anti-racism that makes many populist ideas taboo. For example, when Kellie Leitch ran for leader of the Conservative Party on a plan to screen immigrants for “Canadian values,” she was overtly branded a racist by pundits and rivals.

People will start to resent this suppression “only when there is a breach of etiquette by a successful populist politician, which pulls the centre-right across a norm boundary,” wrote Kaufmann.

In English Canada, the poll by EKOS found about 40 per cent of people think there are too many visible minorities in their communities but “the difference is there are no political vehicles channeling this at the federal level,” Kaufmann wrote.

Taboos are particularly effective at enforcing moral norms because “people act not only on their own beliefs, but from perceptions of what others think is correct,” he wrote. That helps explain why anonymous polling on immigration tends to show more negative results and why norm-breaking politicians like Donald Trump can sometimes inspire what seems like a spontaneous wave of support.

Kaufmann takes care to differentiate between Quebec and English Canada and argues that François Legault’s Coalition Avenir Québec, which was elected on an immigration reduction platform, fits the profile of a populist-right party. The difference, Kaufmann argues, is that English Canada’s historical lack of identity has been replaced with multiculturalism, while Quebec has always maintained a distinct culture.

“Where Quebec identity is territorial, historical and cultural, the contemporary Anglo-defined Canadian identity is futuristic: a missionary nationalism centred on the left-modernist ideology of multiculturalism,” wrote Kaufmann.

Although English-speaking Canadians and Quebecers share similar sentiments on issues that have traditionally been embraced by populist parties — for example, on banning the burka — Kaufmann argued that “the distinct elite norms of English Canada” account for the difference in mainstream support.

“As long as there is no system breach, English Canada may be able to repress criticism of multiculturalism and mass immigration indefinitely,” Kaufmann wrote in his book, published in late 2018. Since then, he fears the system may already have been breached.